Leica Copies Japan

The Leica inspired Canon,

Leica-like Leotax, Nicca & Yashica copies

and the not so Leica-like Minolta 35

(Use sidebar or click on cameras)

Contents

(Scroll down or click on Links)

Japanese Leica Copies - a Potted History

Like a Leica

Identifying Leica Models

The Leica and What Makes a Camera a “Leica Copy”Nippon Kōgaku (the future Nikon)

The End of the Japanese Copies

Leica Post-war Benchmark Models

About

This Page

This page is the entry point to the featured Japanese Leica copies on my site. In chronological camera birth order, they are the Canon, Leotax, Nippon/Nicca, Minolta 35 and Yashica models but as you can see above, that is not quite the order they are featured in. Even though there is quite a lot to be said about the Yashica YE and YF, they are really just a post script to the bigger Nippon/Nicca story and therefore that is where I have placed it. The Minolta 35 makes a nice bookend because it is different, the company alone was already a successful camera maker (not including late buy-in Yashica) and also because Leica and Minolta eventually got into bed together. And, spoiler alert, it falls a little short of the copy definition.

This page is not essential reading to look up information on any of the other pages but for anyone interested, the first part helps understand where the information comes from and whether it is likely to be reliable. The main part seeks to put the Leica copies genre into context and provides a historical overview of how it arrived and developed in Japan. Finally, there is a comparison between Leica and the copies and their respective places in the world. It's not a camera test or feature by feature assessment but more of a philosophical overview of both historical reality and general perceptions.

My Approach

My name is Paul Sokk and I can be contacted by email at paulsokk@live.com.au. My other website is Yashica TLR which is obviously about Yashica Twin Lens Reflex cameras but my first love back in the 1960s was a 35 mm fixed lens rangefinder and I remained an admirer of the elegant simplicity and handling of rangefinder cameras compared to the heavier and clunkier SLRs of the day. In the 1970s, I traded my Minolta SRT 101 in on a Soviet Zorki 4K and some lenses, including my first foray into Leica territory. It was only a short-lived romance at the time but more recently, I have had the opportunity to explore all the possibilities that might have been. I also have an obsession with research and my two websites are the direct result of trying to separate fact from hearsay.

In order to make a difference rather than just create another website about particular models, I have tried to cover the history of Leotax and Nicca to the extent that it is possible and for anyone interested, the early history of Yashica is explored in depth on my Yashica TLR website. Canon and Minolta are already well documented so don't expect anything new or in depth there. I have also tried to provide as much information about the cameras as I can to assist anyone looking for some small detail but note that as I mention on the Canon page, there are plenty of people that know more about Canon than I do. Not everything will be of interest to everyone but if you are looking for something esoteric, hopefully, you will find it.

Japan was home to quite a number of Leica copy makers. The smallest, whilst interesting and collectible in their own right, had little if any impact on the Japanese photographic industry and were wholly for domestic consumption only. These are noted further below. Initially, I focused on Leotax, Nicca, Yashica and Minolta (not in that order) because they had a mid-market presence and they were widely known but information about them was scarce and some of it was plainly wrong. Then I realised that there was an elephant in the room, Canon.

I realised that I had covered all the major players except the one that mattered most; the first, the biggest, the most innovative and the most successful. It wasn't by accident that I hadn't focussed on Canon, there is so much information in books and on websites already, including Canon's own Canon Camera Museum, that I felt that unlike with the other copies, there was nothing useful that I could add. Depending on how you count them, there are around 39 to 43 Canon models plus the prototype Kwanon. That was pretty daunting but then I realised that around 75% of those models derived from either relatively minor updates or mostly from mixing and matching features, e.g. 1000 or 500 top speed; no flash sync, FP & X sync, FP sync only, maybe X sync only; trigger or lever film wind etc. If you count the models designed pre-War as one series, there are 7 separate series or basic designs. In the end, I've decided that I need a Canon page to pay homage to what many think of as the Japanese equal of Leica and to also set the scene for the Leica copies that followed. However, whereas I am fairly confident that my other pages are the most comprehensive and accurate of any currently available, the Canon page is more of an overview and taste, albeit not very brief, and I will endeavour to provide as many links as possible to other sites and useful resources. As usual, one thing I won't do is repeat opinion or not test unsubstantiated claims.

I have used many photos acknowledged as “Detail from larger web images” or similar. These are mostly low resolution, cropped, sometimes drastically, images from completed auctions, usually from Japan. That's where most of the cameras are. I have however used parts of low resolution versions of photos from Massimo Bertacchi's “Innovative Cameras” site to illustrate features of some early cameras, principally on the Leotax page, images that are just not available elsewhere (some of them appear on other sites). Where used, I have acknowledged his site as the source. His site is well worth looking at, for the photos especially, but keep in mind, some of the information is, in my view, suspect.

I am more historian than collector but when I decided to write about these cameras, I acquired examples of each to give me a feel for at least the mainstream, more recent versions and these are featured on the site.

My main tools, as always, are my databases, mainly in the form of spreadsheets tabulating serial numbers of many hundreds of cameras of each of the five makes and all sorts of trim and specification variables. I have not used anyone else's documented serial numbers or ranges from websites nor any of the reference sources unless specifically mentioned. They are serial numbers that I have seen on a camera, obviously mainly in photos. Serial numbers of my and contributors' cameras are displayed in full as are the numbers of publicly displayed rare early cameras. The rest are all those that I have found, mainly on Japanese auction sites, and are displayed with at least the last digit shown as “x” to preserve anonymity. Photos can have up to the last three digits obscured.

I have also tried to find as many ads, brochures, user manuals and related documents as possible, some acquired, some downloaded and some provided by contributors. Some of these are featured on the site, or at least links are provided to sources (more so on the Canon page).

Each of the five pages follows a slightly different format. Some of it is due to my thinking of other ways to present the information but mostly, it is due to the different source material available and the different characters and histories of the companies.

Japanese Leica Copies - a Potted History

Like a Leica

The screw mount Leica is often claimed to be the most copied camera in the world. In terms of sheer numbers of actual copies produced, that is indisputable, although, I suspect that the Rolleiflex/Rolleicord duo from the TLR world may give it a run for its money in terms of the number of makers producing close copies. However, there is no doubting its iconic status and game changing concept and design. Whilst it wasn't the first 35 mm stills camera, nor the first to use the 24 x 36 mm format, it was the first commercially successful one. The design was revolutionary and it created 35 mm photography as we know it, remaining a leader until usurped by its re-imagined offspring, the Leica M3 in 1954. There are aspects of its design, including its cloth focal plane shutter, that continued into the 35 mm SLR era and are still influencing how a camera should be laid out in the digital age.

Replica of Oskar Barnack's 1913 prototype, now known as the Ur-Leica (“Ur” short for both “original” and “prototype” in German):

(Detail from larger web image)

(Detail from larger web image)

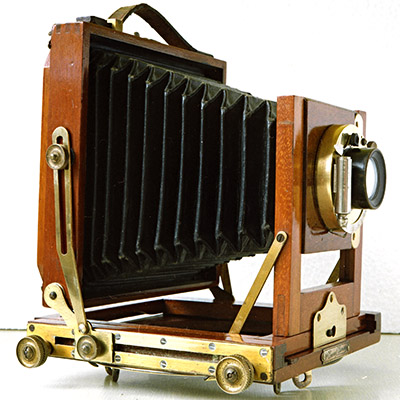

When he designed his prototype, mainstream photography could be roughly characterised by the roll film Eastman Kodak Brownie box camera for the masses, first released in 1900, and folding models such as the Kodak No. 2A Folding Autographic Brownie of 1915, below left, for more discerning buyers and dry plate field cameras such as UK's W. Butcher & Sons Coronet of 1913, below right, for enthusiasts and professionals:

(Right image courtesy of Terry Byford)

Of course, the photographic marketplace was already much more complicated than that with a vast range of quality models from Germany also but formats smaller than the then new 127 roll film (4 x 6.5 cm negatives) were not in common use and 35 mm was only available as bulk movie film stock. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Japanese camera manufacturing was still embryonic and a few years behind Europe, its state perhaps exemplified by the birth in 1928 of the company that later became Minolta and its early focus on roll film and dry plate cameras based on German designs.

In looking at the impact of the Leica from the viewpoint of Japan, I feel conflicted by the omission of the Nikon rangefinder camera, an equal and worthy competitor of Canon with a shared history but based more on the Zeiss Ikon Contax design which itself was a real pre-World War II threat to the supremacy of Leica and some believe would have prevailed if not for the Soviet annexation and dismantling of the Contax factory. True to the Leica designer Oskar Barnack's vision, both the Contax and the Nikon were interchangeable lens precision 35mm cameras with focal plane shutters (the Nikon, with a Leica type cloth shutter, more of a Contax/Leica hybrid camera) but did some key operational things differently and some would argue, better (e.g. removable back for film loading in 1932 and on the 1936 Contax II, combined viewfinder/rangefinder with long base). Indeed, the Leitz adoption of the interchangeable lens system seemed to have been spurred on by the announcement that Zeiss was planning that with its Contax release. Nevertheless, whether it was due to a twist of fate or not, it was the Leica and Leica design that continued to lead the 35 mm revolution and Zeiss is now best remembered as the originator of many of the World's leading and enduring lens designs for all formats. Note, the Contax I had initially proven very unreliable but that was largely overcome with rolling improvements and the release of the Contax II.

The screw mount Leica was, and remained, a minimalist design despite adding some necessary features over time. It was a precision tool but was designed to be as compact as then technology allowed, from it's collapsible lens to its body which was only just big enough to cover the film path from film magazine to take up spool. Copy makers learned to understand the camera but few mastered its philosophy in their rush to make improvements for 1950s consumers. Of course, Leica's own larger M3 let that cat out of the bag.

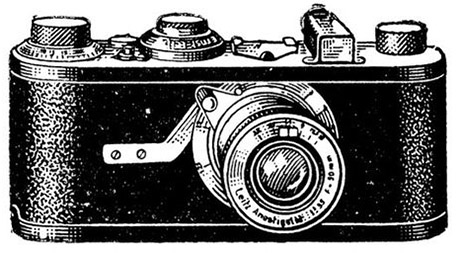

From an early ad for the first production Leica camera, now known as the Leica I (model A), which was introduced in 1925 (only called Leica I when the II was released in 1932):

Apart from the non-interchangeable lens and lack of rangefinder, it was much like the following Leica screw mount models and copies. Correspondent Neal Wellons' lovely example against a period ad:

.jpg)

(Image courtesy of Neal Wellons)

Whilst the 1934 Soviet FED is undeniably the earliest mass produced “true” Leica copy and appearance-wise is almost a carbon copy of a Leica II (basically, a Leica I model C with rangefinder), technically, its slightly different spec lens mount pushes the definition boundaries, more below. The lens barrel is also a faithful Leitz Elmar copy but the optical formula is a Tessar. There were also a couple of obscure predecessors from 1933 connected to the same project. 1938 FED (“1b” collector classification - by this time, the viewfinder window frame had lost its Leica notch and gained the rectangular shape that is the most obvious give away of fake Leicas, Nippons etc):

Not that it would probably have mattered to the Soviets but Leitz had not applied for patents in Russia, or apparently in China, so they were free to do as they pleased. From my understanding, the only “illegal” copy that ignored international patent laws was likely to be the Japanese War-time Nippon (Nicca ancestor), and perhaps, some may argue, that the Kardon developed for the US military during World War II was also an “illegal” copy.

Following the Soviets came the first Japanese makers in the mid-1930s and early 1940s with Canon, Leotax and Nippon models. Post-War, with the USA and Allies claiming German patents as War reparations, they were joined by cameras from the USA (civilian version of the Kardon), UK, Italy and later China (the sometimes included French Foca used a different lens mount, was innovative in its own right and was more inspired by than a copy). Some of these were very well made but it has to be remembered that by the time the later and better copies of the screw mount Leica began arriving, Leica itself was moving to the superior M3. This lovely collection of Leicas and copies is owned by correspondent Neal Wellons:

(Image courtesy of Neal Wellons)

In order from the top and left first: Leica I (model A), Leica II, Leica IIIf, Canon IIIA, Canon III, Zorki (Ic), Shanghai (Chinese), Kardon (USA), Tower (Nicca).

Screw mount Leicas are often called “Barnack Leicas” after the designer. Some would argue that strictly speaking, Barnack Leicas ended with the IIIb, the designer himself dying in 1936 (his last involvement was with the IIIa), and that the 1940 die-cast IIIc didn't fit Barnack's mould. The IIIc didn't move far from the original, except for the new stronger body and one piece top plate design, but the strongest objection to calling it a “Barnack” seems to be the couple of mm increase in size, the designer having been fanatically intent on maintaining the camera's petite dimensions. I'm sympathetic but that nuance is for others to debate. However, whilst inconsequential to many, I am reasonably certain that Barnack would have been completely disapproving of the further size and weight increases of the Japanese die-cast copies regardless of who made them so it would be a travesty to refer to them as “Barnacks”, as some do, just because they share some/many Leica screw mount features.

Identifying Leica Models

Leica model names are a little esoteric. Pre-War, the European and US markets used different naming conventions, e.g. the German Leica II is the US Leica model D, the III is the F and the IIIa is the Leica model G, the last model using the dual names (O.K., not quite, the IIIb seems to have also been called the model G followed by “-1938”). According to the Leica historian and author Gianni Rogliatti, the alphabetic model names were actually the names used within the Wetzlar factory. Why the numeric names were used for European models is not known.

These days, the European convention is mainly used, at least in my part of the World. Leica I, II and III can indicate relative ages of cameras if talking about the most fully featured models available at the time, but they also indicate feature sets. Simplistically, “I” models don't feature rangefinders, e.g. the early Leica I but neither does the last type Ig released in 1957 (companion to the IIIg). “II” models do have rangefinders but no slow speeds, e.g. the 1932 Leica II and the IIf post-War companion to the IIIf. Confusingly, the Leica IIIa and IIIb are stamped body types with rangefinder, slow speeds and a top speed of 1/1000 and a IIIc is a die-cast body with the same specs. Whilst a very significant construction improvement, Leitz didn't consider it a capability/operational change worthy of a major name change.

The Leica and What Makes a Camera a “Leica Copy”

“Leica copy” is an emotive term, particularly for those that believe that their camera is either superior to a Leica, or that it is sufficiently different to preclude the connotation of the word “copy”. “Leica compatible” may be a better term, or perhaps we should just focus on “non-Leica, non-SLR (rangefinder would preclude Leica Standard & Leica I copies) 35 mm focal plane shutter interchangeable lens cameras” - that wouldn't add many cameras and would also capture the Nikon which was influenced by both Contax and Leica. However, for better or worse, the term “Leica copy” was popularised by books such as HPR’s (Hans P. Rajner) “Leica Copies” and Pont and Princelle’s “300 Leica Copies” and that and their definitions is what I decided to go with when I started this site.

So, what is a Leica copy? Leica copies generally follow the design parameters of the German Leica camera designed by Oskar Barnack in 1913 and launched by Ernst Leitz in 1925. A basic criterion is the use of 35 mm film using a 24 x 36 mm frame size (3 x 2 width to height ratio). The Nikon, not a Leica copy, and the Minolta 35 both started with an “ideal” 4 x 3 format of 24 x 32 mm and moved to 24 x 34 mm (the Minolta via an interim 24 x 33 mm) but Nikon succumbed to the Leica standard of 24 x 36 mm in 1954 whereas the Minolta has been claimed not to until at least 1958 but I can confirm that claim is incorrect and the Minolta 35 never did change from 24 x 34 mm (34.5 mm claimed for a short while). The move of the Japanese to the 24 x 36 mm frame size is often directly related to matching the requirements of automatic slide film cutting machines in use in the USA but that is only partly correct. The 24 x 32 mm frame used 7 sprocket holes per frame and that resulted in 40 frames per standard roll/length. By moving to 8 sprocket holes when Nikon increased its frame size to 24 x 34 mm and Minolta made its first move to 24 x 33 mm, the number of frames per roll, albeit smaller, were reduced to 36 and the needs of the slide cutting machines were satisfied.

The shutter must be focal plane - most examples copied the Leica cloth type fairly closely, although January 1958 production of the Canon VT de luxe introduced the stainless steel foil curtains found in later Canon models but these operated on exactly the same principle (as did also the titanium foil curtains introduced on Nikon models).

The first production Leica, model A, did not have an interchangeable lens so Leica copies are usually compared to the model C, now both usually called the Leica I with the alphabetic name in brackets, released in 1930 (the earlier model B featured a fixed lens with Compur leaf shutter instead of the usual Leica focal plane type). That introduced the use of the 39 mm Leica Thread Mount (LTM) with a Whitworth thread pitch (used on microscopes of which Leitz was a maker) of 26 threads per inch and a 28.8 mm lens flange to film distance (nominal, not exactly that until 1931).

Note: Whilst Leica Screw Mount (LSM) and L39 are acceptable alternative descriptions of LTM, the commonly used M39 is not. The “M” stands for metric and M39 uses a thread pitch of 1 mm (LTM is approximately 0.977 mm). M39 mounts are commonly found on Soviet Leica copies and with a different flange to film distance, on early Soviet Zenit SLRs (Braun Paxette rangefinder as well). It is claimed that the Soviets didn't initially realise that Leitz had used a Whitworth thread instead of metric. My Soviet f/2 Jupiter mounts easily on my Leica IIIc but pre and post-War f/3.5 FEDs bind, and would cause damage if forced. They have less of a problem on my Japanese bodies - the tolerances are probably greater. It is also claimed that the Soviet rangefinder camera mounts changed to the LTM standard in the “1950s”, presumably before my Jupiter was made.

The inclusion of a coupled rangefinder is not mandatory for a Leica copy. Some Leica models don't feature them, notably the “I” models and the “Leica Standard” or model E. Black bodied Leica II left and black Leica Standard on the right (similar to Leica I model C):

(Detail from larger web images)

However most Leica copies introduced before Canon's re-imagined 1956 VT end up looking like a typical screw mount Leica with rangefinder, either the earlier slightly smaller stamped and assembled body type or the later slightly larger (2 mm wider, 2 mm taller depending on reference but also as measured by me) but stronger die-cast type with one piece top plate introduced by the 1940 Leica IIIc. With the exception of the Hansa Canon and Canon J, special War-time Nippon with rangefinder housing but no rangefinder, the Leica Standard based early Chiyoca and little known Muley and some early Leica II based Leotax and Chiyoca models, Japanese examples were typically Leica III based with slow speed escapement and separate front mounted slow speed shutter dial.

Early body Leica III/a/b type below left (the IIIa added 1/1,000, the IIIb moved the viewfinder eyepieces close together, not usually found in Japanese early body types), late body Leica IIIc/f type below right (IIIc shown, the 1950 IIIf added flash sync for the first time with a manual flash delay setting dial under the high speed shutter dial to cater for all sync requirements but Japanese die-cast copies typically offered a simpler auto-switching X/FP sync, although the switching on the first die-cast Leotax models, F, T and K, was manual):

(Left detail from larger web image. Note, probably not exactly to scale)

Like its Nippon ancestor, early body Nicca Type-III S still mirrors its 19 year older Leica III inspiration closely with the exception of the added flash sync (usually twin sockets on early Japanese bodies if X sync offered in addition to FP sync):

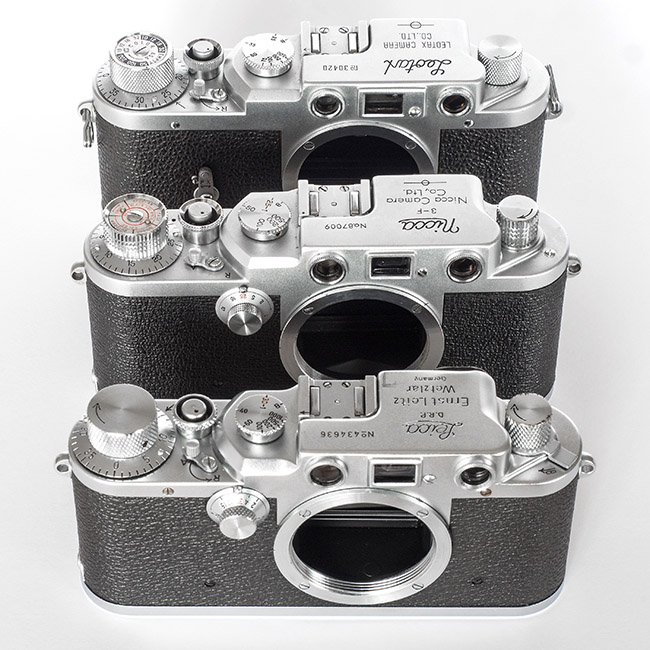

Below is the Leica IIIc inspiration with its close die-cast body copies, the Nicca 3-F and Leotax K (the Leotax K is related to the Leotax F as the Leica IIc is to the IIIc, i.e. they are basically the same camera but without slow speeds):

The Leica is (width x height) 135 x 69 mm, the Nicca 139 x 71 mm and the Leotax 140 x 72 mm. Note, no Leotax model offered dioptre adjustment (the lever under the IIIc rewind knob) and the only die-cast Nicca models to do so are the Type-5 and 5-L.

Some later models made by the copy makers were less clearly related to the Leica III cameras. In 1954, Leitz released a completely new model, the Leica M3, a re-imagined 35 mm rangefinder camera broadly based on its earlier design but completely updated to regain its leadership status and leave the copy makers and the still nascent SLRs far behind, at least for a time.

(Detail from larger web image)

(Detail from larger web image)

Unlike the Leica IIIf and earlier iterations, its design was again protected by patents. The headline features included one of the best parallax corrected viewfinders combined with rangefinder fitted to any rangefinder camera ever, lever film advance, auto film counter, single dial non-rotating shutter speed dial, a flap in the back to aid with the still bottom film loading and a four tab Bayonet lens mount. The bayonet mount was fiercely protected by Leitz but some of the other features were adopted/adapted in various combinations by the copy makers too (although there were some later M mount Japanese cameras, the only actual M3 copy I am aware of was the Chinese Red Flag 20 made in very small numbers in the early 1970s for presentation purposes only). Some of the features were added to existing Leica III-like screw mount bodies but there was also a move to new body styles, invariably involving a “bulking up” of body size, something the M3 itself embraced without embarrassment but for a few of us, one of the few negatives of the new Leica model, the other main one being price.

However, whilst loosing the classic look, these new screw mount models still at heart remained Leica copies even if their Barnack link was mainly limited to the frame size, lens mount and shutter type.

Two Leica Idiosyncracies Which Don't affect Copy Status

Why do screw mount Leicas have three windows and two eyepieces?

Rangefinders themselves have two windows, one for the direct view of the subject which is seen through the single eyepiece and the other with an offset view which is reflected onto the direct view by a movable mirror or prism and when the two images coincide, focus is correct and can either be read off a distance scale, or in later implementations, coupled to the lens. Rangefinders were long established for military and surveying purposes before the first camera with rangefinder focusing appeared. The first camera with a rangefinder was the 1916 Kodak 3A Autographic Special which kept it as a discreet unit separate to the viewfinder, a reflection of the thinking and technology of the time. Leitz developed an accessory version of the rangefinder for mounting vertically in the Leica's accessory shoe invented by Oskar Barnack himself.

The built-in coupled rangefinder of the Leica II released in 1932 was more of a “bolt-on” addition to an existing body with largely fixed positioning of components and controls and Barnack's desire to keep everything within the size envelope of the original which was designed to fit into a coat pocket when coats in Germany were coats (Agfa had possibly been first with an accessory coupled version for its Standard roll and plate film cameras circa 1930 but it was not built-in). Leitz took the vertical accessory rangefinder, turned it sideways and distributed the workings either side of the viewfinder whilst retaining separate eyepieces for each. Also, it may have been an expedient solution to combat the Contax released in the same year, 1932, by arch-rival Zeiss Ikon which featured a built-in coupled rangefinder. In any case, the viewfinder combined with rangefinder hadn't been invented yet and the first 35 mm camera to feature this was the heavily revised 1936 Contax II (the roll film Welta Weltur may have been earlier, 1935 is suggested). Note also the long 90 mm rangefinder base length (and in further comparison with the Leica, the self-timer already and the slow and fast shutter speeds to 1/1250 combined on one dial incorporated into the base of the film wind knob, plus the aforementioned opening back):

(Details from larger web images)

But there was an advantage in separate windows too. Initially, the Leica rangefinder magnification was 1x and this was increased to 1.5x by the Leica III. Camera viewfinders often have a magnification of less than 1x to give a full image of the scene and this obviously applies to the combined rangefinder too. The Contax II is 0.75x. The Canon three level magnification viewfinder (0.67x, 1x and 1.5x) introduced in 1949 confuses the issue somewhat but suffice to say that only the 1.5x position equating to a 135 mm lens angle of view matches Leica III accuracy. Rangefinder accuracy is a product of the base length and magnification and therefore the relatively short 39 mm base of the Leica rangefinder was less of a disadvantage compared to the combined viewfinder/rangefinder and long base length in models such as the Contax II and its Nikon copy. Also, for some subjects, the 1.5 magnification just makes it easier to focus. However, there is no getting around the fact that the Zeiss system was superior and Leitz was slow to react, waiting until it released the new generation M3 in 1954.

Canon and Minolta were already making optical system improvements in the late 1940s, most of the other makers did in the five years after the M3 release.

The other thing is the Leica bottom loading unitary body shell. Leitz was adamant that this produced the strongest body and ensured the film plane remained within specification. The design certainly has the strength to take knocks and falls dished out by professionals, the film plane argument perhaps less of an issue considering the number of successful cameras with opening backs. Even Leitz realised that it had to improve film loading and its solution was the opening flap of the M3 which had marginal impact on body integrity but also, only a small improvement on convenience and speed of loading. Only Nicca (and hence Yashica) copied this idea, most of the copy makers that survived into the late 1950s eventually adopting an opening back, either hinged or removable. Collectors' references still consider these to be Leica copies rather than “inspired by”, “Leica-like”, etc.

The 1947 Minolta 35, later similar Model II below left, already featured a hinged back. Canon introduced its first opening back model, the trigger wind VT in 1956, below right is its 1957 lever wind L2 sibling:

The Japanese Copy Makers

First, a little historical background. By the middle of the 19th century, Japan had been through a period of over 200 years of self-imposed isolation over fears that western influence would tip the delicate balance of power of its feudal system of governing. Directed to establish a trading relationship with Japan, the gunboat diplomacy of US Navy Commodore Matthew C. Perry famously resulted in a 1854 treaty which led to Japan opening up access.

Interest in western advances in optical systems and photography begin to develop quickly. Several camera companies can trace their roots back to the 19th century but it wasn't until 1903 that the Cherry Portable, Japan's first portable camera, was released by Konishi Honten (forerunner of Konica). Lenses for photographic use and similar applications began appearing but the optical glass was imported from Germany and being on opposing sides in WW I resulted in supplies drying up. Japan imported most of its military optical needs like binoculars and periscope and rangefinder systems but with the War, equipment was difficult to obtain from allies as well. Not wanting to rely on foreign supplies in the future, the Imperial Japanese Navy took action to improve the capabilities of the domestic optical industry including starting the development of optical glass manufacturing in 1915.

A munitions optical instrument facility was established in Tokyo on 25 July 1917 to support the Imperial Japanese Navy's needs. With assistance from industrial giant Mitsubishi Group, the company Nippon Kōgaku Kōgyō K.K. was formed from the amalgamation of the previously independent companies Iwaki Glass Seizo-sho and Fujii Lens Seizo-sho and Tokyo Keiki Seisaku-sho's optical division and would eventually become the future Nikon Corporation. A contracted team of eight German technicians arrived in January 1921 to begin production of a range of optical products including microscopes, telescopes, surveying equipment, rangefinders etc. The first camera lenses were designed in the late 1920s and were called “Anytar” for Tessar designs and “Trimar” for triplet designs. In July 1931, Nippon Kōgaku applied to register the name “Nikkor” (an adaptation of “Nikko” which was a Japanese abbreviation for the company name, Nippon Kōgaku) and this was granted in April 1932 (camera-wiki.org). The first production lenses were aerial photography Aero-Nikkors made for the Japanese Army Air Force in 1933.

The camera market was an area that Nippon Kōgaku was interested in exploring and was looking for further opportunities. This was still at a time when many lenses (and shutters) were being imported from Germany - lens quality was higher and often cheaper.

Meanwhile, in another part of Tokyo, Seiki Kōgaku Kenkyūjo (Precision Optical Instruments Laboratory, the later day Canon) was formed in 1933 and in 1934 designed the first Japanese precision/focal plane 35 mm camera and sort of Leica copy. This was the Kwanon prototype, named after the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy.

The production version released in 1936 (some say 1935) was renamed Canon but is known as the Hansa Canon because “Hansa”, a trademarked brand name used by the camera's distributor, Omiya Shashin Yohin Co., Ltd. (meaning Omiya Photo Supply), usually appears above “Canon”. The hexagonal body ends of both the Kwanon and Canon cameras became a signature feature of all Canon interchangeable lens rangefinder models.

Whilst undoubtedly Japan's first production precision and/or focal plane 35 mm camera, the first production 35 mm stills camera of any type may have been the 1935 or 1936 “Super Olympic” fixed lens/leaf shutter type with Bakelite body with equally uncertain release date. Also, with production came a name change from Precision Optical Instruments Laboratory to Precision Optical Industry, Co., Ltd., “Seiki Kogaku Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha”.

The production camera was somewhat different to the Kwanon with lens, focusing mount and rangefinder system now designed and made by Nippon Kōgaku. These were significantly changed to avoid infringing Leica's Japanese patents for these items granted in 1934. Instead of the Leica mount's 39 mm thread with a pitch of 26 threads per inch (TPI), the Canon featured the same 39mm diameter but with a pitch of 24 TPI and a focusing mount was screwed into this and secured by set screw. The removable lens barrel was inserted into it using a bayonet mount, somewhat similar to the Contax mount.

The viewfinder arrangement was also different, the rangefinder windows were in their expected positions but the viewfinder itself was a pop up type. The large dial on the front was the frame counter left over from the initial Kwanon design with the winding knob on the front:

(Detail from larger web images)

Pre-War introduced Canon models continued to be different from Leica because of patent concerns. The 1939 budget model Canon J without rangefinder and slow speeds eliminated the expensive Nikon focusing mount and instead used the 39 mm 24 TPI screw mount directly in Leica fashion but of course was not Leica compatible. This was referred to as the “J mount” and also used immediately post-War.

With German patents no longer an issue, the first post-War designed model was the Canon S II released in October 1946. Even with the signature Canon angled body ends, it otherwise looked very similar to a Leica III except for the first major innovation, the rangefinder and viewfinder were combined and there was a single viewfinder window. It was supplied with Seiki Kōgaku's newly developed “Serenar” 5 cm lenses, initially an f/3.5 followed by the option of an f/2, although early on, there were still some Nikkor f/3.5 lenses as well. Canon S II with Serenar f/3.5 5 cm lens from shortly after the maker name change to “Canon Camera Co.”:

Peter Dechert, respected Canon guru and author of “Canon Rangefinder Cameras 1933-1968”, tells us that the Canon S II featured a mount referred to as “semi-universal” which was close to the Leica standard but would accept the earlier J mount lenses as well as most Leica lenses - to make it work, the threads were cut sloppier. The rigid barrel f/1.8 50 mm Serenar, developed during 1951 and released with the Canon IIIA and IV F in January 1952, was the first Canon lens with “universal” mount, meaning it was finally fully Leica compatible.

Seiki Kōgaku became Canon Camera Company Ltd. on 15 August 1947 and changed again in early 1951 to Canon Camera Co., Inc..

The real innovation and major success came with the next model, the 1949 Canon II B, which added three level magnification to the viewfinder (lever under rewind knob) and was a unique Canon feature appreciated by photographers until the Canon P changed direction in 1959:

The importance of Canon to this story cannot be overstated. As well as being the genesis of the precision interchangeable lens 35 mm camera sector in Japan, it was Canon's (and by now, Nikon's too) mid-1950s innovations that the smaller makers like Nicca, Leotax, Melcon and Tanaka were trying to keep up and compete with, not so much the Leica M3. The M3 was more Canon's and Nikon's benchmark. Whilst the other copy makers had already fallen by the wayside, in September 1961, Canon launched its most successful model yet, the Canon 7, which took the shutter coupled accessory Canon Meter 2 of recent models, patterned on the Leica M3's Leicameter, and built it in. The frame lines were projected rather than the earlier reflected type and the lens mount included an external bayonet for the optional f/0.95 50mm lens:

(Image courtesy of Chris Whelan)

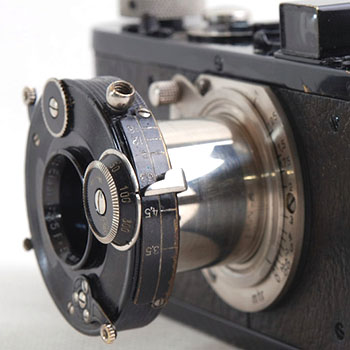

Back in 1937, future Yashica lens maker, and eventually acquisition, Tomioka (perhaps in association with Sankyō Kōgaku - Camera-wiki.org), produced several prototypes (Lausar and Baika) of what looked like a rangefinderless Leica copy complete with 5 cm Leitz Elmar-like collapsible lens and focal plane shutter but it wouldn't qualify for the purist definition because it used 127 format roll film in a 3 cm x 4 cm portrait format (the 35 mm type re-wind knob was in fact a dummy for appearance sake). Also, the small diameter spindles would have created film flatness issues which would have been difficult to overcome. Nevertheless, Riken Kōgaku Kōgyō, the future Ricoh, announced a very similar 3 cm x 4 cm 127 model, the Riken No.1, in 1938 and sold it as the Gokoku in 1939 and 1940 and followed it up with a revised model called the Ricohl. Tomioka Lausar with Lausar 5 cm f/4.5 lens:

(Web image)

(Web image)

Also in in 1937, Takachiho, the future Olympus, advertised and produced 10 prototypes of a hybrid Contax/Leica (somewhat akin to the 1948 Nikon) called the Olympus Standard but using 127 film for a larger 4 cm x 5 cm landscape format, requiring a 65 mm standard lens which was mounted in a Contax/Hansa Canon/Nikon style focusing mount. It was a beautifully made and engineered camera with combined rangefinder/viewfinder but as a result of technical difficulties with the larger upscaled Leica type focal plane shutter and film flatness, as well as cost, it didn't proceed further. Although Seiki Kōgaku offered 50 mm Nikkor lenses for its Canon cameras in different aperture sizes and also developed a War-time Serenar 135 mm prototype, choices of different focal lengths for Japanese cameras didn't become a reality until after the War (there was a pre-War Nikkor 35 mm lens in Canon mount that some say was a prototype, but Nikon says “it was used in a device for recording numbers of telephone calls”). However, the first ad for the Olympus listed 3 different aperture 65 mm lenses, a wide angle 50 mm lens and a 135 mm lens. All in all, the Olympus Standard was a remarkable aspiration for its time. Note, viewfinder in centre, rangefinder window on right:

(WestLicht Auction photo)

(WestLicht Auction photo)

Following Canon, the next near-Leica copy was the 1940 Leotax made by Shōwa Kōgaku. It looked more like a Leica than the early Canons did but to avoid patent issues, the rangefinder was not initially coupled and it and the following iterations used viewfinders and rangefinders with odd window arrangements and mechanisms until after the War. Leotax Original with uncoupled rangefinder (see distance dial at rear of housing) and typical example of first three Special models with coupled rangefinder:

(Left image, Ryosuke Mori & KCM Library, right image Camera Collectors' News December 1978)

Whilst Shōwa Kōgaku also sourced its standard lenses from Fujita (the Letana Anastigmat fitted during the War), Konishiroku (the later Konica) and Fuji Photo Film, its main supplier of lenses was Tōkyō Kōgaku (translated as Tokyo Optical Company), maker of the later Topcon SLR and War-time supplier of optical products to the Imperial Japanese Army.

The bodies were Leica II and III-like until the Leotax F introduced die-cast construction and the Leica IIIf look in 1954. An improved viewfinder and lever wind were the only substantial changes until the Leotax G almost arrived as a Canon competitor in 1961 when the company was already bankrupt.

1957 Leotax TV with improved bright frame viewfinder and self-timer for the first time:

1961 Leotax G:

(Detail from larger web image)

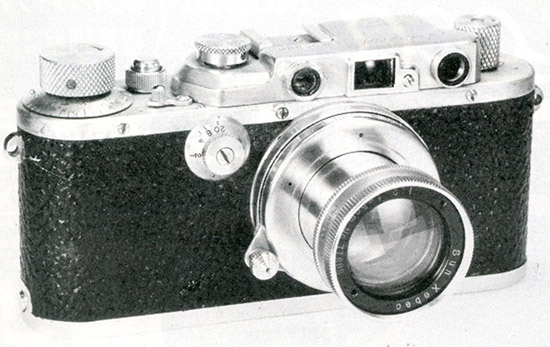

Approaching the War in the Pacific, quality German cameras became difficult to obtain and in 1941, the company that became Nicca, Kōgaku Seiki-sha, was given a military order to develop a faithful Leica copy. The principal of the company had worked for Seiki Kōgaku (Canon) and the Canon distributor had helped him set up a Canon repair facility. The camera was named Nippon; and the first example was delivered in 1942. Below is a 1948 Nippon with notched window (earlier ones were identical except with rectangular windows) and the rebranded Sun Xebec f/2 5 cm collapsible lens (similar to original K.O.L. Xebec):

(Image from Mikio Awano's article in Camera Collectors' News, August 1978)

In 1948, the Nippon morphed into the Nicca and until 1955, the very Leica III-like camera evolved slowly, the biggest advance being the introduction of flash sync. Then in 1955, Nicca also introduced die-cast construction and the Leica IIIf look but went one step further with a sort of Leica M3 film loading trapdoor, except hinged sideways. This was updated to lever wind and a more M3-like top hinged trapdoor. With a much improved single window viewfinder/rangefinder added, the final model was released in 1958 at about the same time that Yashica acquired the company.

1955 Nicca Type-5:

1958 Nicca III-L:

(Image courtesy of Mr. Cheyenne Morrison @BigShotPhotos:)

Whilst Nicca didn't show a lot of innovation and stuck closer to the Leica formula than most, the cameras have a good reputation for quality. Perhaps more importantly, they (along with smaller and later arrival Melcon) were supplied with Nikkor lenses with a full range of focal lengths offered by the distributor, Hinomaruya.

Aside from Canon, which developed its own unique features and style, and the Nikon, if considering interchangeable lens rangefinder cameras rather than just Leica copies, Leotax and Nicca cameras are generally considered to be the best engineered of the rest. However, perhaps the Minolta 35 introduced by Chiyoda Kōgaku Seikō in 1947 should also be in the mix.

The Minolta 35 seems to be ignored by some commentators, perhaps because by some definitions it is on the margins of what is considered to be a true Leica copy. As noted further above, it never did match the 24 x 36 mm Leica format despite claims by some illustrious sources that at least the last version, the 1958 Model IIB, was compliant. It's not the prettiest or the most petite so it would hardly endear itself to Barnack fans. Unfortunately, few have survived until the 21st century with shutter curtains in usable condition but nevertheless, in the late 1940s it was a better mousetrap with combined viewfinder & rangefinder already (i.e., single eye piece) like the just released Canon S II, 7 years before the Leica M3. It featured a hinged back door (rare at this time and probably the first on a Leica copy, if it can be called that, just beating the Italian Sonne IV), the first self-timer on a Japanese camera and an early form of hot shoe flash synchronisation utilising the accessory shoe central pressure ball, probably inspired by the 1938 US Univex Mercury (replaced by a plug socket on the back of the 1951 Model E and later variants). Flash sync only arrived on the Leica models with the 1950 IIIf.

Chiyoda Kōgaku may have been “persuaded” into precision 35 mm camera manufacture as a means of earning desperately needed export dollars for Japan but it was also busy with many other models and formats and by the 1950s, the Minolta 35 and its quite limited lens portfolio and system capabilities didn't seem to receive the attention it may have deserved. Model II example from maybe 1954 (opening back shown further above):

The next two models indicate that some Japanese designers were thinking outside the box and were prepared to try some new ideas. Circa 1949 (according to Sugiyama, some claim 1952 or 1953), there was a brief appearance by the Look camera made by Nittō Seikō. This has the appearance of a Leica copy, and is sometimes referred to as one, but it doesn't qualify based on our earlier considerations. In fact it probably has more in common with the 1950 German Voigtländer Prominent usually credited as the first interchangeable lens 35 mm leaf shutter rangefinder camera. The shutter is behind the lens but it isn't at the focal plane. The interchangeable lens mount is not LTM (only the standard lens was ever offered). The focusing mount is actually fixed to the body and the lens screws into that, much like the Minolta A series cameras with interchangeable lenses from a few years later. Rather than Leica's lever operated rangefinder coupling, the Look uses an external geared connection to one of the otherwise “normal” looking rangefinder windows:

(Detail from larger web image)

(Detail from larger web image)

The camera designer was Kaoruju Chatani whose claim to fame is that, in 1952, he patented a metal focal plane type shutter that would be the forerunner of the Copal Square shutter, developed in 1960, and most modern shutters. Apart from being a technical design curiosity, the Look is not a significant model, however interestingly, although at least some were fitted with a Lunar lens, most of the few found examples, including the one above, feature Rokkor lenses made by Chiyoda Kōgaku Seikō (Minolta) (same f/2.8 45 mm lens as fitted to the Minolta 35 but in a unique mount). The Look also features an accessory shoe with central round pressure ball very similar to the early Minolta 35 hot shoe type except that its one curved corner is mirror reversed. Like the Minolta, it is almost certainly a hot shoe, there is no sync socket for a plug and an ad displays a flashgun mounted. The flashgun appears to be similar to the Minolta model but but the shoe is centrally located whilst the Minolta's is offset to the side. Whether a coincidence or not, they both have a front plate for the lens mount. Nevertheless, whilst some of the design elements seem familiar, the lens is the only certain known connection.

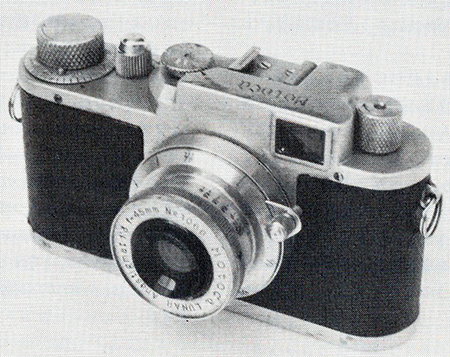

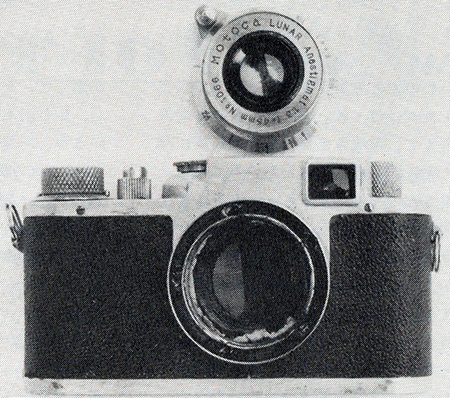

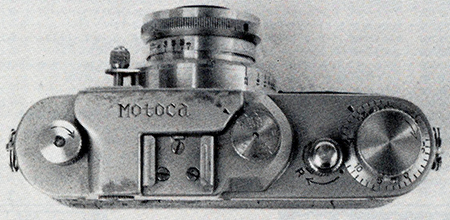

Another almost Leica copy candidate is the bottom loading Motoca 35, as named in ads, or Motoca, as engraved on the top plate, which was announced in September 1948 and advertised in Japanese magazines from September 1948 to August 1949. Although there was no rangefinder or slow speeds, it was laid out in Leica fashion and the one piece top plate gave it the appearance of a Leica IIIc. The frame size was the 4 x 3 ratio 24 x 32 mm “Japanese format” used by the original Nikon, Minolta, Olympus and other 35 mm cameras, and is the only feature that has so far been confirmed to knock it out as a true Leica copy. The lens mount is an unknown type, although it appears to be a screw mount. The lens itself is a 45 mm f/3 with close focusing abilities. Whilst the shutter is not a Leica cloth type, using two metal blades instead, a period ad confirms that it is a focal plane shutter. Speeds are B,1/20 to 1/300. The ad also claims, “the usage of the Motoka is the same as that of the Leica.” According to Camera-wiki.org, perhaps less than 100 examples were produced. The images below are from the May 1982 edition of Japanese magazine Camera Collectors' News. The camera's lens number is 1066 which is the same lens (and presumably body) as in Sugiyama's book:

It was also around this time that the first Muley was made. Along with the early Chiyoca, their claim to fame was that they were the only two Japanese made Leica Standard copies (i.e., without rangefinder housing). Only one example is known to still exist of the Muley Standard type with virtually no information about it other than can be gleaned from the camera itself. The “Made in Occupied Japan” on the base plate suggests that it was made between 1947 and 1951. Sugiyama also features the slightly later Leica IIIc/IIIf rangefinder copy version, presumably die-cast, with opening back mentioned in camera-wiki.org. It is very unlikely that there were any significant numbers made.

The just mentioned Reise made Chiyoca first appeared circa 1951 as a viewfinder only model, then later with rangefinder and finally with a name change to Chiyotax (later produced as the Alta by a different company, Misuzu Kogaku Kogyo). Then followed the Tanack (1952), Melcon (1955) and Honor S1 (1956) cameras, the first two with opening backs, the Honor with removable back. Apart from the backs, they were faithful Leica copies but some of the later models did things differently, e.g. both the Tanack SD and the Melcon II copied the Nikon but used Leica lens mounts and the Honor SL was a copy of the Canon L1/L2 as were the Tanack V3 and VP (all with crank rewind but 1/500 top speed). The Tanack was unusual in that its small maker offered a range of Tanar lenses that seemed to be made in-house.

Below is an ad from the February 1958 Asahi Camera magazine. It features the Tanack IV-S bottom right and the new SD bottom left. The IV-S has a one piece top plate like the previous IIIS models but the first type featured a seperate rangefinder/viewfinder cover like the Leica II and early III models. The lenses featured are; f/1.5, f/2, f/2.8 and f/3.5 50 mm; f/2.8 and f/3.5 35 mm; f/3.5 100 mm and f/3.5 135 mm:

.jpg) (Click on ad for larger version)

(Click on ad for larger version)

From the first model in 1952 until the company's bankruptcy in December 1959, some 16,000 cameras are estimated to have been produced (collating camera-wiki.org pages for all models). Several of the lenses were also offered in Nikon and Contax mounts.

As we shall see on the Nicca page, there was a link between the origins of Nicca and the company that became Canon. In a similar way, the designers and founders of Reise (Chiyoca and Chiyotax), Tanaka Kogaku (Tanack) and Meguro Kogaku (Melcon) seem to have been early employees of the company that became Nicca. Also, Genji Kumagai, designer and a key player in the establishment of Nicca, seems to have been involved with the Daiichi Kogaku developed Ichicon 35 (and the related later Jeicy made by himself) on which it is thought (based on his claims) that the similar Mejiro Kogaku made 1956 Honor S1 was based on (according to Camera-wiki.org, Genji Kumagai left Nicca in 1948 but respected author of “Canon Rangefinder Cameras 1933-1968”, Peter Dechert, in his monograph, “The Contax Connection”, seems to mistakenly claim he remained there as President until 1959 but that doesn't fit with other evidence and an interview Genji Kumagai himself gave in the 1970s). There is a gulf in volume produced between these more recent, really boutique, makers and the Nicca and Leotax cameras, e.g. whilst the most prolific of these, Tanaka, is estimated to have made 16,000 cameras over 7 years, Reise made maybe a total of 2,500 Chiyoca and Chiyotax models, Meguro is estimated to have made 2,300 Melcons between 1955 and maybe the end of 1957 and there may have been around 2,500 Honor cameras made by a complicated list of developers and makers (perhaps developed by Daiichi Kogaku which became Zenobia Kogaku in 1956 with production undertaken by Mejiro Kogaku which was then absorbed into distributer Zuihō Kōgaku Seiki).

The main advantage that these new, and likely under resourced makers offered, with the exception of Reise (Chiyoca/Chiyotax), over their main competitors making more traditional Leica copies was the easier film loading with opening, or removable, backs, something already pioneered by the Minolta 35. Reise stuck to copying the earlier Leica designs and relied on price. However, many of the earlier examples from these makers lacked engineering finesse and suffered from production quality issues. They arrived late at a time that Canon and Nikon were innovating and established 35 mm makers Nicca, Leotax and Minolta were starting to struggle with their already mature models. Making an impact on a crowded and difficult market would be a challenge in the best of circumstances. Arguably, the later Tanack SD and Melcon II which combined the reliability and relative simplicity of the Leica shutter, the simplicity and economy of the Leica lens mount and the vast array of suitable lenses for it with the longer rangefinder base of the Nikon (actually based on the Leica design rather than Contax but with combined rangefinder/viewfinder) were among the finer Leica copies made (albeit featuring the Contax look of the Nikon) but it was too little too late, they weren't bargains at a time when Nicca and Leotax were looking at ways of reducing prices and neither of them were successful sales wise. Meguro disappeared in 1957, the year of the Melcon II release. Tanaka struggled on with Canon L1/L2 copies instead until 1959, the same year the Honor SL Canon L1/L2 copy was released and failed. Both had been based on their earlier bodies with new superstructures added. Who wanted to buy a facsimile, very likely inferior, of a superseded 1957 Canon in 1959?

Of the early Leica copy makers, only the older and more prolific Chiyoda Kōgaku Seikō (Minolta) and Shōwa Kōgaku (Leotax) are known to have made other camera types (apart from the Leotax Leica copies, Shōwa Kōgaku made various versions of the Semi Leotax 4.5 x 6 cm folder from 1940 until 1955, the little known Baby Leotax 3 x 4 cm folder during the War years and the very short-lived Gemflex subminiature pseudo TLR released in 1949).

Nippon Kōgaku (the future Nikon)

Whilst the Nippon Kōgaku made Nikon rangefinders are not Leica copies per se, they were competitors to both Leica and Canon and the company had a very important role in the Leica copy category in addition to its early partnership in the Canon camera project. For the record, the 1948 Nikon 1 copied the Contax II look and used its focusing bayonet lens mount but with a different number of turns of the internal focusing helicoid to match the Leica standard and retain compatibility between Nippon Kōgaku's own S mount lenses for the Nikon and the same lenses produced in Leica mount - it had been using the Leica focusing standard for the early Canon lenses and it produced LTM lenses from 1946 through to the beginning of the 1960s. The Nikon also used the Leica cloth focal plane shutter type (later with metal curtains) and modified Leica style rangefinder so at least as Leica-like as the Hansa Canon and Canon S with their Nikon supplied, Contax inspired, focusing mounts, although, as noted earlier, it wasn't until the Nikon S2 released in 1954 that Nippon Kōgaku adopted the 24 mm x 36 mm frame size. 1950 Nikon M (externally basically same as Nikon 1):

(Detail from larger web image)

(Detail from larger web image)

(Note: Whilst the appearance is similar to the Contax II pictured further above, the positions of the focusing wheel and rangefinder window on the left are reversed. Although the rangefinder base is shorter, the Contax position was more awkward to use and the user's fingers could easily obscure the rangefinder window. Zeiss solved the problem in 1950 by placing the focusing wheel of the Contax IIa behind the rangefinder window. Also, the Nikon's Leica-like shutter uses a separate shutter dial with slow speeds on a separate tabbed dial under it, the Contax II combining the shutter dial with the film wind knob.)

The Nikons would eventually prove themselves as highly desirable and successful professional level cameras at least on par with Canon and perhaps even better built but Nippon Kōgaku's greatest contribution was its Nikkor lenses.

In addition to the early Canon bayonet and J mount lenses, Nippon Kōgaku starting making LTM lenses in 1946 and later both Nicca and Melcon adopted Nikkor 5 cm standard lenses and Nikkor wide angle and telephoto lenses were marketed by their distributor, Hinomaruya, both in Nicca's and Melcon's advertising material and separately as also Nippon Kōgaku's LTM distributor. Nippon Kōgaku introduced its own S mount lenses in 1948 and at some point, also made a small number of fully compatible Contax mount lenses.

The Nikkor lenses debut on the world stage is generally credited to starting with American Life magazine photographer David Douglas Duncan. Whilst Duncan was on assignment in Japan in June 1950, Japanese photographer Jun Miki, a Life stringer, took a casual available light portrait of him with a Nikkor 85 mm f/2 lens mounted on his Leica camera. Duncan was so impressed that he and another Life photographer, Horace Bristol, met with Nippon Kōgaku. The result was that they replaced their personal lenses with Nikkors. When the Korean War started, Duncan used a brace of Leica IIIc cameras also fitted with Nikkors. The higher contrast of the Nikkors yielded noticeably better newsprint output than the comparable Leica lenses. Helped by a feature article in the New York Times, this caused a sensation amongst photographers. Whether they were better or not overall, they certainly worked better for the medium. On the other hand, their quality was undeniable and for the majority of people, the Nikkors simply outperformed their German counterparts of the time in terms of price/performance ratio.

The End of the Japanese Copies

Although it would take a few years yet to play out fully, by the mid-1950s, the Nikkors and then also Canon and other lenses signaled the beginning of the end of the world-wide dominance of the German photographic industry and the beginning of the rise of the Japanese with other well regarded Japanese lenses starting to be recognised as well. Rather than copying the game changing Leica M3 released in 1954 (apart from adopting some of its features for their LTM bodies), the Japanese began to accelerate the changeover of leadership through a new found enthusiasm for developing the SLR from a niche product to mainstream mainstay of both professionals and photography enthusiasts alike. There was also the increasing competence and convenience of fixed lens leaf shutter rangefinder cameras at the bottom end, many of them with superior combined viewfinders/rangefinders and easier to use features such as opening backs for film loading. Finally, as competition intensified and margins shrunk, copy makers like Leotax and Nicca were disadvantaged by not having their own lens making capability. This both affected the price they could charge and cut them off from a significant revenue stream and also made it more difficult to diversify into other categories like SLRs and cheaper fixed lens models.

It's something that I hadn't considered earlier but it seems that Canon's success also strangled the remaining interchangeable lens 35 mm rangefinder market. By the start of the 1960s, most of the Leica copy makers had exited the market, or were about to, but in 1961 Canon released its most successful model yet, the Canon 7, and its updated successor, the 7s lasted until 1968. Even Nikon had decided to concentrate on SLR development and production and to discontinue its rangefinder cameras in 1959, although limited runs of existing models continued until 1965.

In 1959, into the now very difficult interchangeable lens rangefinder marketplace stepped Yashica with its Nicca based YE and YF models. In 1960, it too departed for the SLR world.

In more recent times, there have been attempts to revive the LTM rangefinder with the bespoke Yasuhara T981 arriving at the end of 1998, or beginning of 1999, and Cosina releasing the first of its Voigtländer Bessa models in 1999. Rather than being copies, they were more a modern 35 mm rangefinder camera designed to take advantage of the vast stock of excellent LTM lenses available to rangefinder enthusiasts. Neither survived long, although the versions of the Bessa with Leica M mount were available for a few extra years. The reality is that the world had moved on and the digital era was just around the corner.

Leica Post-war Benchmark Models

Whilst the first examples of the Japanese copy makers were closely based on the 1930s Leica II/III design, the benchmark for comparison of later versions were these three Leica screw mount models spanning the 1940s and 1950s:

Leica IIIc (released 1940, post-War 1946 version below). New body introduced die-cast construction which was eventually adopted by all the major Japanese makers. Available with Elmar f/3.5 5 cm or new Summitar f/2 5 cm lens (pictured) replacing earlier Summar:

Leica IIIf (released 1950). Improved IIIc released with flash sync (hence the “f”), film speed reminder in winding knob and self-timer added in 1954. All these features were adopted in some combination by most Japanese makers and this is the model that most heavily influenced both Nicca and Leotax design in the mid-1950s. New and improved lenses featured including the superior Summicron f/2 5cm lens replacing the Summitar:

(Image courtesy of Terry Byford)

Leica IIIg (1956 - 1960). Improved IIIf with simplified flash synchronisation, larger viewfinder with projected parallax corrected frame lines for 50 mm and 90 mm lenses and film speed reminder moved to the back. The improved viewfinder on the classic styled body may have influenced the 1957 Leotax TV. This one fitted with accessory Leicavit base featuring trigger film advance (origin in the 1930s) which was first copied by Canon and then built into the 1956 and later Canon VT models:

(Image courtesy of Chris Whelan)

However, after introducing die-cast construction and flash sync themselves, as noted earlier, the camera that most influenced Japanese innovation was the 1954 Leica M3, in particular the large combined viewfinder/rangefinder with projected frame lines, single non-rotating shutter dial, lever film advance and “easier” film loading:

(From larger web images)

No one adopted the bayonet mount (the Tanack V3 introduced a 3 tab version but still only offered screw mount lenses with an adaptor) and no viewfinder matched the quality of the M3's but arguably, the hinged backs of models by Minolta, Canon and some of the smaller makers were a better solution than Leica's. Leica disagreed, maintaining the flap style opening all the way through into the 21st century, although adopting hinged backs on its film SLRs.

The lovely example below has an accessory shutter coupled Leicameter mounted. Canon adopted this idea with its Canon Meter introduced with the VI-L and VI-T models in 1958 and building it into the 1961 Canon 7:

(Image courtesy of Terry Byford)

The Comparison

Inevitably, comparisons are made between the Leica and its imitators. There are two separate issues at play. Firstly, there is the ideological. The whole original/pretender dichotomy, the iconic stature of the original, the cult following, the long list of eminent photographers using one, and equally on the negative side, the perception of a plaything of the wealthy, even back in the 1930s etc. Secondly, there are the actual cameras themselves.

Icon

I have already mentioned that the Leica camera invented 35 mm still photography as we know it and it still influences design today. Digital cameras don't have to look like the the body is only there to separate the two film chambers - it's a natural and comfortable way to hold a camera. But it was more than just the camera. Back in the day, you couldn't go to your local store and buy a prepackaged cassette of 36 exposure film so Leitz introduced the reloadable film cassette which inspired Kodak to introduce their 135 format disposable cassettes in 1934. Later FILCA version, similar to original:

The humble accessory shoe was invented by Oskar Barnack for his 1913 prototype to mount his removable viewfinder, later an uncoupled rangefinder and other accessories. Leitz was also at the forefront of offering and developing film loading tools, darkroom tools such as enlargers and developing tanks and slide projectors. Accessory shoe on Oskar Barnack's personal Model O pre-series camera, similar to that on several prototype Leica versions:

(Detail from larger web image)

(Detail from larger web image)

Leitz was also a lens maker and its principal lens designer, Max Berek, was responsible for designing the legendary, and much copied, collapsible Elmar (including its 5 element forebearers) and subsequent pre-War lenses that kept Leica at the forefront of 35 mm photography. The Elmar barrel design was also used by various makers for Tessar formula lenses. Whilst the superb bigger aperture lenses released by Zeiss for its Contax may have initially outgunned Leitz somewhat and the post-War Nikkors gave Leitz a fright, its lens designs from the 1950s onward have been equal to any. Well used Elmar example:

(From larger web image)

(From larger web image)

When we think of what Leitz introduced to the photographic world, we invariably think of Leica cameras with focal plane shutters and interchangeable lenses. The Leica I (model B) still featured the original design's fixed lens but replaced the focal plane shutter with a Compur leaf type - that was the basic template for the tens of millions of 35 mm fixed lens viewfinder/rangefinder cameras produced from the 1940s until the digital age:

(Detail from larger web images)

The Leica was a seismic shift in camera thinking and execution and the design brilliant for its purpose. However, to be successful, it had to be well engineered and built and so it was. The Ernst Leitz company had its origins in a mid-19th century business called the “Optisches Institut” (Optical Institute) focusing on microscope manufacture. By the end of the 19th century, Leitz was World renowned for its microscopes. In that context, the Leica was never going to be a launch by a brilliant but struggling upstart, or cheap - it had all the advantages of large pool of designers and engineers and a skilled labour force. The engineering challenges were understood and accommodated. Marketing and sales departments were in place. There was already a New York office. The company had standing, it was establishment.

The Leica's Place

Although the Leica deserved and achieved widespread success, it turned the approach to photography upside down and was therefore slow to be accepted by many professional photographers used to larger formats and Leica use by them tended to ebb and flow, e.g. after gaining acceptance pre-War, much of WWII reporting reverted to press cameras but Leicas prevailed during the Korean conflict. The early adopters tended to be well heeled amateurs and members of the social set. Whilst Zeiss Ikon released the competing Contax models, the real battle for professional use was still with larger format cameras and then the SLR arrived with its ability to easily mount long focal length lenses to capture close ups of sport and animals in the wild and revolutionise news reporting. From that point forward, the Leica became more of a niche product but the film and subsequent digital M series cameras have managed to survive and even prosper. There is still much appeal for photographers but sales have also depended on it being a collectible status symbol.

There are many photographers, both past and present, professional and amateur, who have been absolutely passionate about their Leica and using its many attributes to the full. They couldn't care less about its bling value or the digital era's Hermes, Zagato or other editions. However, most are not average Joes, you still need deep pockets to buy an “ordinary” Leica. Many say something like, “you don't need lots of money, you can buy a 65 year old film camera, something like a IIIf and still experience the wonders of the camera and the Leica lenses”. Yep, but once you add a lens and a good chance of needing a clean, lubricate and adjust (CLA), you're starting to look at a $1,000 entry fee, at least in Australian dollar terms, at a time when you can find a decent usable film camera for $50 or thereabouts. You have to be a real enthusiast, with some spare change.

So whilst the Leica is without question iconic and one of the most important cameras of the 20th century, there is little doubt that it has always had an aura and social status, and hence price, which elevated it above the means of many an average photographer.

The Japanese Competition

The origins of the Japanese copy makers featured on these pages couldn't be more starkly different. Whilst Seiki Kogaku was initially established with the lofty ambition of competing with Leica and Contax, the Canon camera didn't really come close until the end of the 1940s (the Canon II B and first accessory lenses). The Canon and subsequent Leotax and Nippon cameras soon became Leica substitutes in relatively mundane roles in a country that was endeavouring to be strategically independent as conflict began to engulf it. Apart from Seiki Kogaku, with its head start and collaboration with Nippon Kogaku, and Chiyoda Kogaku Seiko, responsible for the post-War Minolta 35, they were mostly start-ups with access to few resources. Whilst a Leica could be pulled down, examined and copied, the skills, engineering and production methods had to be learnt on the go. In comparison to Leitz, the facilities and production tools would have been primitive and the scale tiny. Design was by trial and error and as confidence and resources grew, by the 1950s, innovations were being introduced which started to separate the copies from the original.

From humble beginnings, the Japanese cameras developed into good quality photographic tools, fit-for-purpose. They were competing in a tough market with lots of options and the SLR starting to emerge. There was no ability to charge premium Leica-like prices and therefore the quality of engineering and attention to detail couldn't possibly hope to match Leica levels, particularly in the case of the smaller makers like Nicca and Leotax. The niche makers even more so. But to the user, much of that is not visible, nor perhaps even material.

Except for Canon and Nippon Kōgaku with its hybrid Contax/Leica, the Japanese copy makers couldn't afford to, and didn't, offer a wide range of accessories. Neither could they offer the Leitz levels of support and factory service nor even anything more than any other Japanese camera maker of the day.

Even though the earlier Japanese Leica copies look like Leicas, their worlds and market positions are at opposite ends of the spectrum. Well maybe not so much Canon and Nippon Kōgaku which in the end, really did produce better cameras, meaning similar quality, easier to use and cheaper than screw mount Leicas and even challenging the M3 in some respects, but the others were certainly not competitors of Leica. They were more everyman's cameras whereas the Leica was the aspiration of both makers and buyers alike.

Part of the Leica legend are its lenses. Not every one has been stellar in ultimate resolution and other metrics but they have all been very good for their time, had a consistent look to their colour and rendering and have been exceptionally well engineered for smooth operating reliability and long life. For a little while, Nikkor lenses got people excited in terms of their resolution and rendering but it didn't take long for Leitz to rise to the challenge even as other Japanese lenses became recognised. Whilst Nicca used Nikkor lenses, professionals and well heeled amateurs during this period of Japanese ascendency were more interested in using the Nikkors on their Leica bodies than buying a Nicca. Leotax offered lenses from various makers, Tōkyō Kōgaku (Topcon), Konishiroku (Konica), Fuji Photo Film and even Olympus but while most of these seem to be well regarded, compared to Leica, there was limited choice in focal length and the consistency of “look” was certainly absent as was the Leitz attention to engineering.

However, leaving aside lenses and the other natural advantages of Leica, what are the real differences between operating a screw mount Leica body and a 1950's Japanese made copy? By all accounts, not a great deal if you are comparing like with like, particularly bottom loading models. Many Leica examples have been well used and need a CLA if they haven't had one in more recent times, many copies have been badly stored for many years and may also need a CLA. In fact copies seem to have fewer problems with their shutter curtain longevity (except Minolta) and also their rangefinder prisms. Unfortunately, whilst both the original and copies would benefit from a CLA, the Leica one is often treated as a necessary expense of buying an old Leica whereas the copy is equally often begrudged one, not the least because people buying them don't often have the same wherewithal as those buying the more expensive camera, but sometimes just because the copy costs much less in the first place and a CLA will easily double the purchase price. In the real world, the Leica is much more likely to return the investment in a CLA than its copy.

There have been, and are, photographers that prefer the convenience of the later Canon rangefinders and those that believe some Nicca examples approach Leica quality. The Leotax, particularly prior to the die-cast models, is perhaps less kindly considered in that regard. On internet forums, people who have good things to say about the copies usually also have experience of Leicas too, or still have both. Those that argue strongly on behalf of the Leica over the Japanese copies are more often doing it from an ideological perspective, not from user experience.

The Leica deserves to be revered and that is one of the reasons that it retains its high value for collectors even though there are many in existence. For the user, it shouldn't be a question of one or the other, there is no reason why bodies and lenses shouldn't be mixed and matched and appreciated simply for the final image the photographer captures. The experience is very similar, the differences are more nuances. The Japanese copies really did become very good and even though most did not survive beyond the 1950s, they were at the forefront of the Japanese revolution that eventually overtook Germany as the home of the leading photographic industry in the world. Their history deserves to be told and they are worth preserving for what they are and represent.

I can't resist adding a final point to comfort those offended by the idea of copied German technology. How did Germany achieve technological and engineering greatness? Obviously a lot of hard work but that came on the back of a period of technology transfer. Whereas for a long time, “Made in Germany” has been an assurance of excellent quality, premium products and accompanying high prices, the origin of the “Made in Germany” product identification was an 1887 British law enacted to help consumers identify the importation of “inferior” German products.

.jpg)